JAKARTA: Two months before this week’s presidential election in Indonesia, prize-winning novelist Eka Kurniawan declared in an opinion column that “the Islamists have already won”.

Unofficial results from Wednesday’s poll show that incumbent President was actually the winner and is set for a second five-year term – but they also reveal a hardening bloc of conservative Muslims who voted for his challenger.

Widodo’s commitment to pluralism in the world’s largest Muslim-majority country may have narrowly won him the race. But the Indonesia he must govern is now more polarised by religion, and he may struggle to meet the demands of Muslim groups that backed him and fend off more hardline Islamists who did not.

“In the short term, Widodo will have to accommodate the opinions and interests of the Muslim-majority because, if the majority feels insecure, it is difficult to protect minorities,” said Achmad Sukarsono, a political analyst with Control Risks.

“This is just being pro-people. It doesn’t mean Indonesia will turn into Saudi Arabia or that the country will go straight to amputating a hand for theft.”

While nearly 90 percent of Indonesians are Muslim, the country is officially secular and is home to sizeable Hindu, Christian, Buddhist and other minorities.

Some fear Indonesia’s tradition of religious tolerance is now at risk, however, as conservative interpretations of become more popular. Among myriad measures of this, demand for sharia finance is growing and more women are covering their heads or donning full veils in public.

ISLAMIST FORCES

Widodo’s rival, former military general Prabowo Subianto, buttressed his challenge by forging an alliance with hardline Islamist groups and religious parties to tap into this trend.

Unofficial results show that not only did Prabowo maintain support in conservative strongholds like Aceh, West Java and West Sumatra – he won four more provinces that had gone to the incumbent when he ran against him in 2014.

These provinces are seen as among the most conservative because they have introduced sharia-based by-laws and their demographic make-up is more than 97 percent Muslim. Prabowo won in at least 13 out of 34 provinces in Wednesday’s election.

Analysts say such divisions are here to stay.

“This election has produced a more divided political map,” said Eve Warburton, a research fellow at Australian National University. “When Widodo and Prabowo are no longer on the front line, divisions may mellow but they will not disappear.”

Prabowo has complained of widespread cheating and is threatening to contest the results.

Many of the hardline Islamist clerics and groups backing Prabowo’s presidential bid were the same as those who in 2016 and 2017 led mass protests to topple the ethnic-Chinese, Christian governor of Jakarta, , a one-time close ally of the president.

Widodo, at risk of appearing anti-Islam, distanced himself from Purnama, who was eventually jailed for blasphemy. He also launched a systematic campaign to woo the country’s largest moderate Muslim organisation, Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), and to appeal to Muslim voters by appearing ‘more Islamic’ himself.

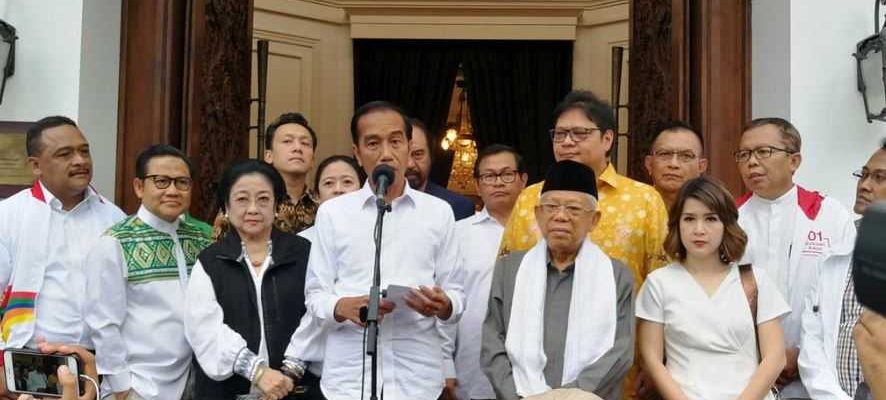

But the president shocked more moderate and progressive supporters when he chose as his running mate NU scholar Ma’ruf Amin. As chairman of the Indonesia Clerics Council in 2016, Amin issued a fatwa banning Muslims from joining Christmas mass, and his testimony helped convict Purnama.

Nonetheless, Amin helped in the eyes of some voters to remove any doubt about Widodo’s commitment to Islam and neutralise the overall threat to Indonesia’s official secularity from groups gunning for an Islamic state.

One presidential aide, who spoke on condition of anonymity, said that as vice president, Amin, who is an expert on Islamic finance, was expected to “have an important role, particularly on religious issues and policies”.

But aides are confident of Widodo’s ability to “handle” the demands of religious groups that helped propel him to victory.

“The president can embrace (the religious forces) with all kinds of social and economic efforts, but at the same time he will be forceful to reject their agenda to change the ‘Pancasila’ in any way,” the aide said, referring to the country’s secular ideology.

“VICTORY FOR MODERATE ISLAM”

Hardline groups that were once on the fringes of Indonesian politics, most notably the Islamic Defenders Front (FPI), have increasingly muscled their way into the mainstream and arguably provide a political voice for conservative Indonesian Muslims.

The FPI and similar groups call for an Islamic state, with Islamic law for all Muslims in the country.

That may be popular with many voters – according to a 2017 study by the Pew Research Center, 72 percent of Muslims favour making sharia the official law.

But for prominent moderate Muslim figure and Widodo campaign adviser Yenny Wahid, the election nonetheless represents a victory for moderate Islam.

“Widodo will be bolder now than before in sealing off space that Islamists have tried to occupy in politics and social life,” she told Reuters. “It is time now for moderate Muslims to consolidate based on the election win.”